Show Your Work!

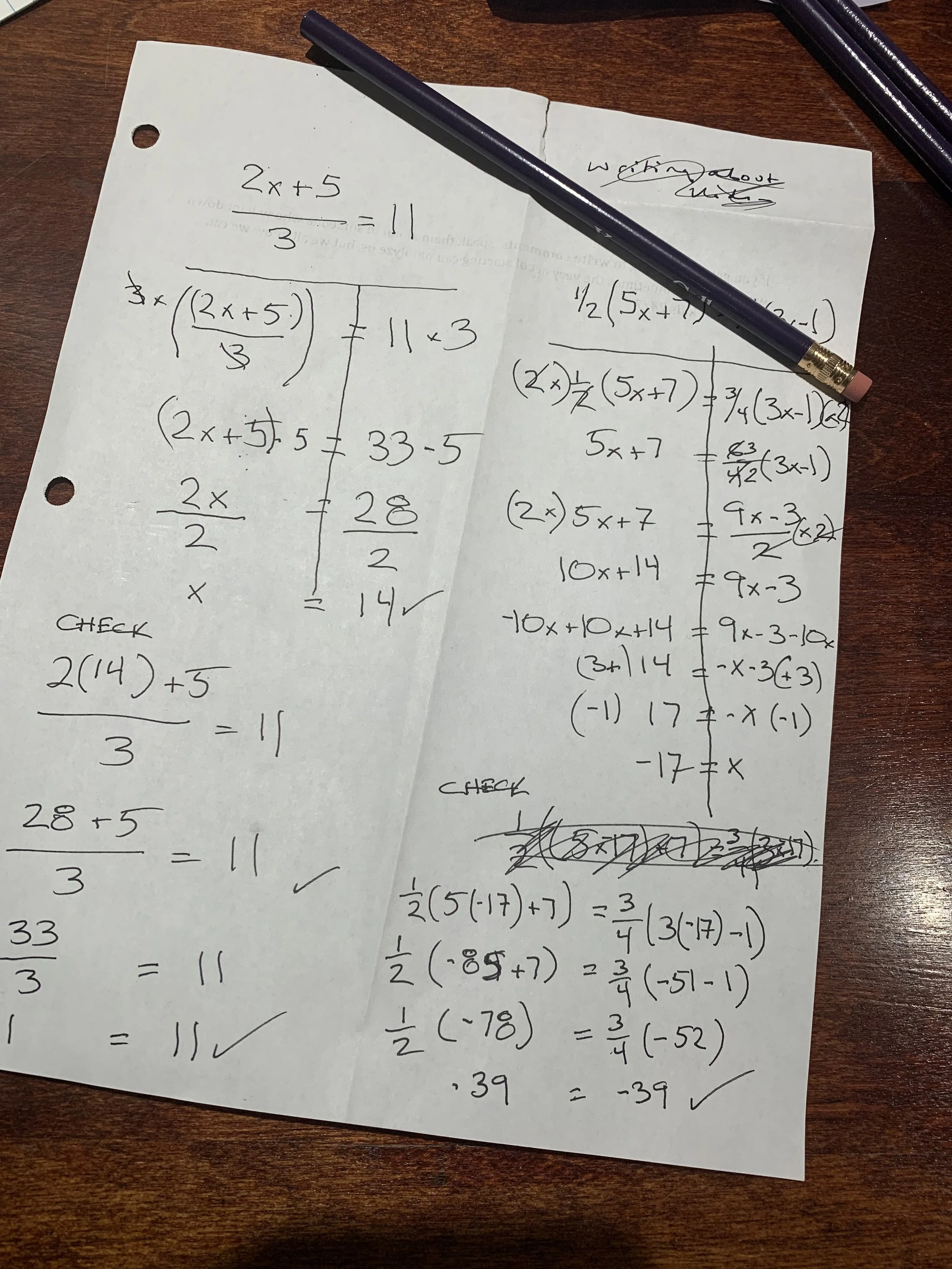

As a little girl–and even as a high school student, math teachers would chide me, “Show your work, Ann. Show how you got that answer.”

“Ugh,” I’d think, rebellious. “It’s so tedious to have to do all that. Can’t they just see that I got the right answer?”

Of course, I hadn’t always gotten the right answer–as a school girl or later as a school leader.

By not showing my work, I prevented my teachers from seeing where I’d gone wrong or made a faulty calculation; they couldn’t help me see my confusion or even give me partial credit if they didn’t have a window into the way I’d tried to solve a problem. Over the years, I got a little better at showing my work, but it always felt like an extra step until I led a school.

I have always assumed that everyone with whom I work knows what I know, and, in fact, the people with whom I’ve had the privilege of working have known a lot. But knowing a lot doesn’t mean everyone is in my brain with me or everyone understands my rationale, the problem I’m hoping to solve, or the process I went through to arrive at a particular decision when I don’t tell them!

Sometimes, in meetings, faculty would raise basic questions because it’s their first exposure to a new idea or initiative, and I’d feel irritated because I’d been considering all those questions for months in hours of meetings with the folks who had been at the table. But not everybody is at every table–especially when it means hours of meetings. Sometimes, as leaders, we simply want to get where we’re going. The destination seems so clear; we’ve stewed about it for days, maybe months, but we have to share our rationale. The reason for the new idea–the why, if you will–must precede the what or how.

People can only absorb information when we share it. At my best, I’d anticipate the basic, honest questions and respond with patience. At my worst, I fear my exasperation showed, but like wine or cheese, I got better with time. Meeting questions undefensively, with a spirit of curiosity, is one way to model leadership. Giving people information in clear and timely ways, so they can take it in and think it through is a hallmark of a thoughtful leader.

“Go slow to go fast,” a mentor once urged me, but I chafed at that paradox, which feels like a first cousin to “show your work.” I’m a fast processor, reaching conclusions swiftly and expecting others to do the same. Fast isn’t always helpful when you need a whole group to move with you in shared understandings of the why behind a what.

The final product matters, but the process of how you get there matters, too. Slowing down has never been intuitive for me, but when we slow down, we make time for nuance, complexity, shared understandings. Often, we get more specific when we have to pause to explain ourselves and the end result may be stronger because we encourage tough questions, allow colleagues to wonder with us about pros and cons, to have a window into what our process was.

Three times in the past week, I’ve suggested to coaching clients that they need to “show their work.”

“Take time to articulate the thinking that got you to where you are now,” I urged. “Remember, people aren’t mindreaders. What’s intuitive or obvious to you may not be to others. It’s always worth it to explain your rationale, to invite people to poke holes in your grand idea. You want others to join you in whatever it is you are hoping to achieve, to walk with you on the quest. Remember, if a leader gets out too far ahead of her troops, she begins to look like the enemy.”

Each time I offered a version of that speech, the client paused.

“I thought they understood all that…” one client trailed off.

“You did, but they didn’t. Go back, take the time to start over. You won’t regret it,” I said gently. A trustee with whom I collaborated on a strategic plan long ago encouraged me to review how we had gotten to where we were–essentially to review the time line–every time, with every constituent group.

“Won’t they feel like imbeciles when I repeat the entire process every single time?” I asked.

“No,” she said. “They don’t remember. They’re not inside the process the way you are.”

And she was right. They were not inside the process; they were on the outside looking in. That wise trustee was another version of a math teacher urging me to show my work.

The marvelous team of Kawai Lai and Meghan Cureton came to school some years ago to facilitate a session with our leadership team.

“Make the implicit explicit,” they counseled.

I’ve reflected on that wise advice ever since their visit. I’ve been reflecting on all that is unstated but understood in schools–the subtext as it were. So much is implied but never spoken, and that fascinates me, but I’m a drama teacher by training, so I like wondering what’s simmering underneath what’s said aloud. Not everybody enjoys that kind of puzzle. It’s no crime people hope their boss will say what she means and mean what she says, but when we are not explicit, we leave too much open to speculation, misinterpretation. People make up theories or justifications when leader aren’t clear; they jump to conclusions and all they imagine may muddle things and make more work for the leader. Be deliberate; shape the process from the start. Avoid being a control freak, but do consider how new ideas may land given the larger school context. Are people feeling overworked? Underappreciated? Will the new idea help them or be perceived as “one more thing.” Think about timing; think about who you can shine light on when you share the new idea.

As a school leader, showing one’s work means being explicit, being clear, being willing to test drive a hypothesis or a vision or a policy before implementing it. It’s not, I’ve learned, ever a waste of time. It’s an investment in the people around you. Sharing your process is a way to better understand a blind spot or bias. The times when I wanted to skip right to the end with a top-down decree were often the times when my leadership wobbled–you need to bring folks with you whenever you can. Investing in clarity is always worthwhile.

Thinking back, I should have been thanking those math teachers. They were right all along.