Advent: Waiting, Listening, Looking Forward, and Sensing My Mom

For the most part, I am a summer Episcopalian, a faithful attendee at 8:00 a.m. communion—no hymns—at St. John’s in the Wilderness in Eagles Mere, tucked into a pew next to my sister, the green glass rectangles in the window to our left—olive, mint, leaf—a reminder of our community’s roots as a glass factory. We always sit house right—the right hand side of god—about a third of the way back from the altar. I love that church, love that service, know it almost by heart. I read the lessons in July, think about our mom, in between us for many years, gone now since 2010. She was a December baby like me, so she has been much on my mind of late. I imagine celebrating what would have been her 90th birthday. I’ve been a little weepy, missing her.

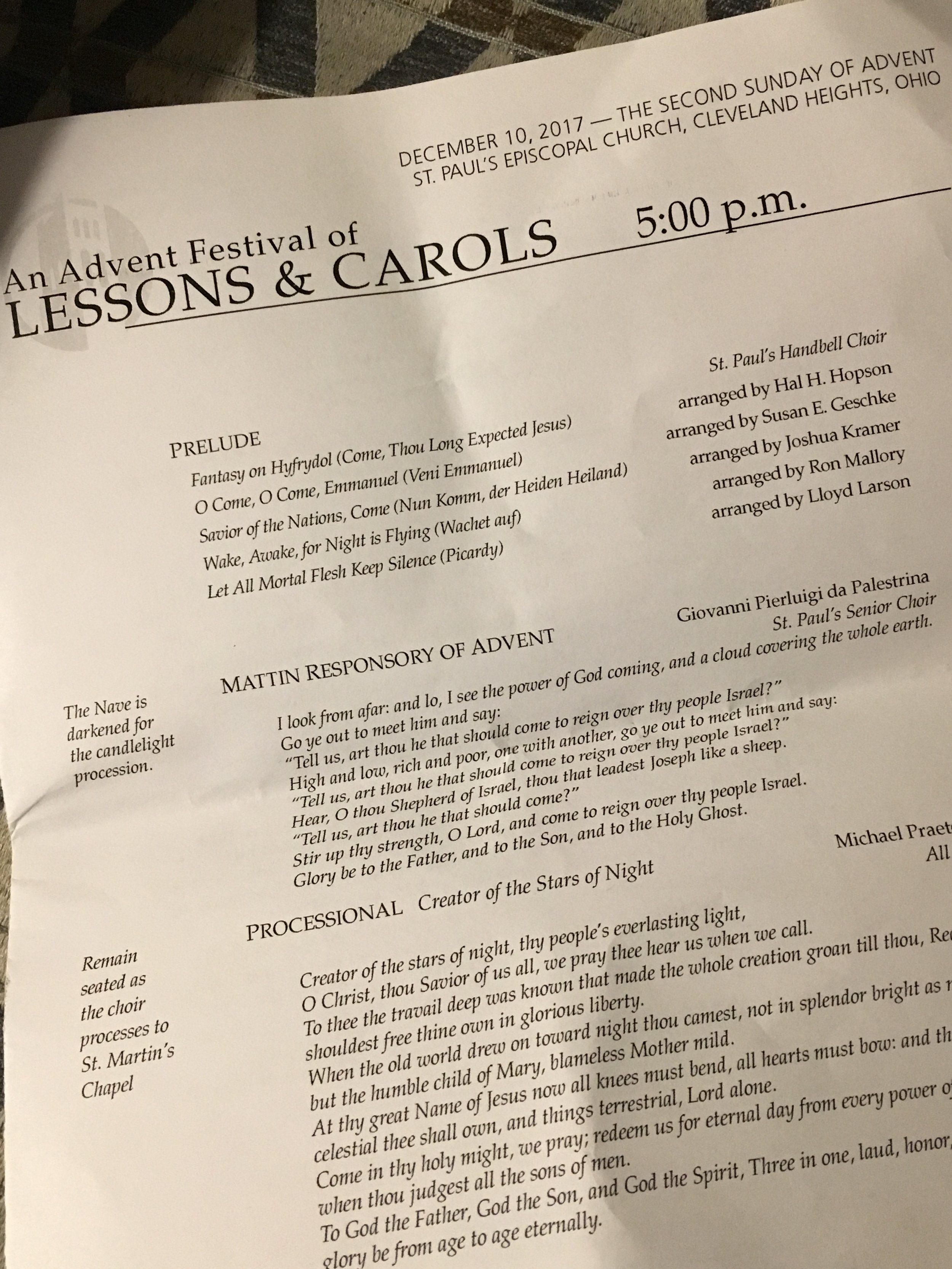

On Sunday, I went to St. Paul’s in Cleveland Heights, the church I would attend regularly if I did attend church regularly during the school year. It is Anne and Joe’s church, and I love that they invited me to the Advent Lesson and Carols Service, one in which I have participated several times as a guest reader. We were early enough to listen to the hand bells, their silvery notes floating through the sanctuary. I removed my hat and coat, knelt and bowed my head, thinking about my mother, wondering if she prayed as I do, listening mostly and breathing in the familiarity of church. I settled back into the pew, checked my phone to be sure it was turned off, breathed and admired the Advent Wreath. Advent is about anticipation, a pregnant woman awaiting a birth, a count down.

The candles on the altar flickered in the air currents. The nave was dark. Suddenly, I have just turned fifteen again; it is Christmas Eve, and I am the first dark-haired angel in the Christmas Pageant at the Church of the Redeemer. A pity angel, I think. I stand on a plinth in the front of the church, swathed in a costume made from a white sheet, tinsel garland crossing my chest to support my wings. I hold my arms up and they feel leaden. My brother has been dead since early August. I know the congregation is murmuring: “The angel on the right—that’s Cooie’s daughter. So nice they chose her after all that sadness—though she is a brunette. That’s a break with tradition. But you know—her brother and that car accident.” That’s what I imagine, watching the shepherds—my friend, Whit, is one--straggle down the aisle, and then the Wise Men processing with a nobility golf-playing dads don’t often conjure in blue blazers and khakis. One of the three kings has frankincense and, as he swings a ball, the pungent fragrance wafts throughout the church—the smell of Christmas. As long as I was a pity choice, I wish I had been Mary, but I’m only in tenth grade, and Mary is usually a Senior. She gets to hold a real baby. My mother grimaces at me from a pew. “Smile,” she mouths. I feel faint. I worry I might throw up or pass out. While I love theatre, this feels like work. And I can’t even see the star. The best part of Advent at the Redeemer is the star, glowing way up high in the nave above the altar, right beneath the eaves. It was a long time before my father explained there was a light bulb up there illuminating the star. I thought it was magic.

Back to the present, the handbells finish and the choir at St. Paul’s in Cleveland Heights processes. My eyes travel up, seeking the star. It is not there, but my mother, gone now seven years, seems to be--not in some creepy, ghost-y way, just as if she felt like dropping in for the service and happened to land next to me. I can almost smell her Chanel #5, the Cryst-o-Mint lifesavers she favored at church. I hear her voice in my ear--strong, melodious, buoying me up. Our mother loved to sing and loved Christmas. In the swell of the rousing O Come, O Come, Emanuel and The Angel Gabriel—I hear her: “most highly favored la—dy.” In the thrum of the Lord’s Prayer, I note her inflections as if I am tucked in again, a child, next to the chilly silk of her mink coat, against which I used to lean my cheek.

“Take heart,” she urges me in the words of the hymns she knows by heart. “We are waiting together.” And, at the end of a long week, I am comforted. The congregation seems to lean forward, singing with gusto, carried along by the expectations of the season, by hope and joy. I’m not alone. I blink at the tears that betray my family gene for weeping at the weirdest times.

Mary was so young. I’m not sure I would have been thrilled if the Angel Gabriel had appeared in my kitchen to tell me I was going to have a baby even though Joseph and I weren’t yet married. I’m pretty sure I would have freaked out—even though the news of my cousin Elizabeth’s miracle pregnancy would have been exciting. I smile; in fact, with my history of infertility, not to mention Atticus’ arrival in my forties, I identify more with Elizabeth than with Mary.

I am a Christmas baby, born on the 23rd, the worst present he ever got, according to my brother, Rod. In those days, moms stayed in the hospital forever, so on Christmas Day, Daddy brought Lee and Rod to see me, not into the hospital, but to be held up to the window, so they could glimpse me from the parking lot. Allegedly, I had a lot of hair. This is my season. I wrap the familiarity of the Episcopal liturgy, a cloak of my mother’s devising, around me briefly. Babies and evergreens and lights and crèches and trees and wreaths and presents and memories and snow. And hope. And the unexpected echo of our mother in church, with me.